|

Sometimes it all goes by and you just want to grab it. |

|

The colors of the sea as the afternoon ages into night. The rich

musk-like smell of the earth coming out across the salt water

as you near port after five days on the ocean. |

|

Pelicans skim over the waterline at suppertime. Just grab it.

You know it's a sad thing to think that way. That you need to

keep it, stop it, not let it go. Sadder that it's just damned

impossible to do it. |

|

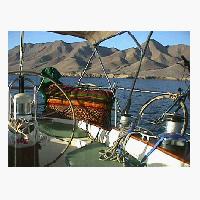

We sailed and motored eleven long days trying to reach the moonscaped

islands and craggy mountains surrounding La Paz, Mexico. |

|

One long stretch, really, 900 miles down and around the tip of

Baja California Sur. |

|

Sleeping in shifts, through the cold of night, dodging freighters,

trying to make port by Christmas. It was beautiful. It was hell,

too. |

|

Sailing southward a few nights out from San Diego an iridescent

yellow blip showed up on the radar, coming in slowly toward us

like a missile seeking ground zero. An ocean going freighter

slicing northward at thirty-five knots forty miles off the Mexican

coast. Jon radioed the captain. Sylvia woke up and watched as

the big ship closed the distance. The captain acknowledged us

in a Russian accent, said he saw us on his own radar. He kept

coming, though, closer and closer, plowing the dark seas. We

could see his running lights, red and green. You see that, the

red and green, and you know you've got close to a dead hit ahead.

Sylvia turned on the masthead light to illuminate our sails against

the dark ocean swells. We called out again. The captain came

over the vhf radio sounding panicked. He'd seen another boat

on radar, five miles distant. He mistook us for that ship. Now

he could see the Aviana visually dead-on in his path. The giant

steel vessel, lit brightly, maneuvered, cranked over,best it

could. It was just enough. The ship and its freaked-out captain

slid past a freaked-out us and into the night. |

|

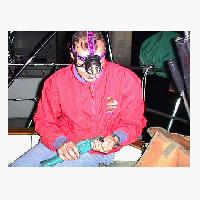

We wouldn't have had that radar if Dan Roy in San Diego hadn't

given up his family and his free time to install all the specialized

equipment needed for an extended ocean voyage. San Diego is a

cruiser's trap. The sirens' lure. You get in there and you're

lucky to get out. We arrived feeling good. A pleasant port of

call. We left just about broke and broken spirited.

Cruisers in Mexico laugh when you tell them you stopped in San

Diego to outfit your boat. "The Trap," it's called.

Once in you can't get out. Boatyards quote you a price for work

and a week later what you pay bears not even a slight resemblance

to the estimate you hold in your trembling palm. Marine businesses

suck you in, start the installation, then disappear as they shill

for more business while you sit and wait for someone to show

up to finish the job. And sit. And wait.

Dan Roy. If you're in San Diego on a boat, pray that Dan Roy

rides in out of the dust, just when you thought you couldn't

stand the sorry situation another second, straps on his head

flashlight, and saves your day. He did ours, fixing other technicians'

mistakes, getting us on the road to Mexico finally, pointing

the way with a wrench and an index finger to our high seas adventure

south.

|

|

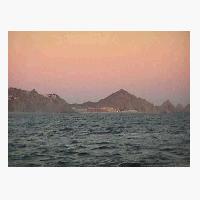

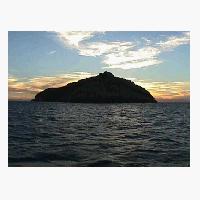

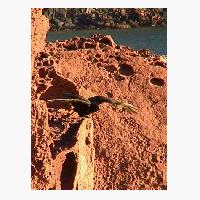

The first islands north of La Paz, in the Sea of Cortez, rise

out of the sea like the dead volcanoes they are. Rocky. The moon

with an atmosphere. |

|

Beaches too. White sand and clear water. |

|

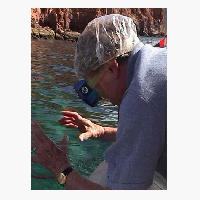

Christmas we headed to Isla Espiritu Santo, Island of the Holy

Spirit, with Jon's mom and brother, the irrepressible Vi, and

Jay, the wry observer. |

|

Mom Dunc half dove, half snorkeled, butt-up, in the cold clear

water.

What she saw, we'll never quite know. We wouldn't believe her

even if we understood her garbled speech trying to describe through

a snorkel the enormity of the underwater world.

A fine thing that Jay came too. Mom and Sylvia couldn't have

pulled the weight of that raft through the shark infested shallows,

their soft dainty ankles gnawed away to bony nubs.

|

|

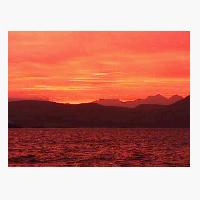

This is what you want to hold, to grab. Put your arms around

the sky and pull it in. Each time you see it you wish you could

just keep it. Every night it slides into the black.

You breathe deep. You pray. Tomorrow, please, God, tomorrow.

Give me more.

|

|

You go to sleep here anchored alone in a cove. You wake to find

another boat, fishermen, taking the cover of land to block the

rocking swell of the sea. |

|

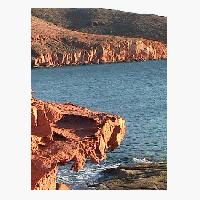

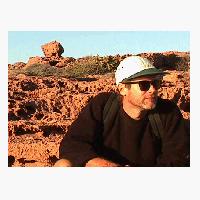

We spent a month and a half in and around La Paz. A favorite

inlet wraps around Aviana like a warm volcanic sheet.

The land and the sea. Like southern Utah with an ocean lapping

the flanks of its red rocks. The weather in January warms you

but rarely overheats. The wind sometimes blows like Zeuss on

a rampage, like witches on the attack, like you better find cover

or the gods and the goblins will sweep you clean off the deck.

Fifty knot winds swept up one day off Isla San Francisco, churning

twelve to fifteen foot breaking seas, sending our twenty thousand

pound boat careening like a surfboard down the swells. We lost

a dinghy that day and an outboard motor. Both torn away with

the violence you can only know after having seen. We tethered

ourselves to the boat and thanked the fates once we reached a

protective cove that we hadn't lost each other.

|

|

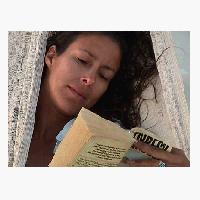

January, Steve Jerve, television meteorologist, came to visit.

Came to visit the hammock, anyway. Man, he loved that thing.

Wouldn't let us lay down for a second. |

|

He finally got out at one point to use the head. We locked him

in. |

|

That hammock felt good without Big Steve taking up space. |

|

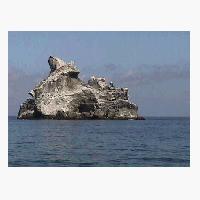

Isla Isabella stands as a few guano covered rocks about eighty

miles south of Mazatlan, thirty to forty miles off the Mexican

coast.

Not much there except birds and the evidence they leave of

their presence.The Mexican government has declared the island

a sanctuary for the winged fishermen. |

|

If you've got a boat and you're nearby, you'll find sooner or

later a hitchhiker stopping to take a ride. |

|

Pelicans. Herons. Gulls. They all live off of pescado, or fish.

This was the point in our trip, nearly two thousand miles since

we started, where we began to live off fish, too. Tuna practically

jumping onto the lines we dragged in the cresting seas behind

the Aviana. |

|

Clean a tuna and it'll bleed like you severed an artery in your

arm. Sink a blade into its flanks and you might as well be slaughtering

a lamb or a calf. The first few bites of your meal carry the

memory of murder. It's not fun, frankly, but that didn't stop

us from mixing up wasabi and slapping on the pickled ginger and

letting that fresh raw fish flesh slide on down our throats.

Tuna for breakfast. Sashimi for lunch. Tuna on the grill for

dinner. The steak of the sea, tuna is firm, flaky. Excellent

in every way. Don't ever try to tell us, though, you can't have

too much tuna

|

|

Captain's log

Feb. 18, 1999

N 21.32 W 105.17

Coming into San Blas I felt as though we'd sailed into Africa.

Banana plantations and coconut trees running up jagged green

mountains made dimensional by wisps of fog and the smoke from

cooking fires. This is where the rain forest begins in Mexico,

about 22 degrees north latitude. The air clutches you. The sound

of strange birds. Roosters, too.

It's 6:30 a.m. and those roosters are the reason I'm sitting

here. Starting at 4 they don't stop until everybody's up. At

six the church bells start to ring. We're anchored up a river

just across from the rusting tuna boats of San Blas. There's

a reason we're here, too

We'd been at Isla Isabella, a stopover island most of the way

down from Mazatlan, about 40 miles out in the Pacific. About

six miles out from San Blas, 30 miles north of Puerto Vallarta,

a measured voice, somewhere in the octaves between tenor and

baritone, sounded from the radio. "We are Jama. We are here

to help cruisers..." It could have been Jim Jones. It was

entrancing. I couldn't not jump on the radio to reply. I seriously

considered that it was a recording played in a constant loop

and that we'd just gotten into range. "We are Jama..."

Africa. Jama. This was getting interesting.

Jama was a man, an American, a "we" who claimed to

want to help cruisers. I still assume he's just a cruiser who

got stuck in the mud of the estuary here 33 years ago, and the

ghost of his living self still needs to feel the "cruising"

connection.

"Evian," he mispronounced Aviana, "we invite you

to take the estuary into San Blas...", instead of anchoring

out in the awe-inspiring Mantachen Bay, the very bay I described

at the beginning of this letter. Jama was persistent. Jama was

a San Blas salesman. He wanted us up the river like he wanted

me to be his Captain Willard. Oh, the horror.

We anchored out in the bay that night, the tide being too low

to go up-river to San Blas. By morning, after a couple of cafe

con leches and a healthy dose of what is now a never ending feed

wagon of fresh tuna, we motored in.

Not too many sailboats had come up this way. What with the looks

we were getting from panga skippers that was obvious. Entering

the narrow breakwater, trying to time the surf, breaking swells

very nearly threw us onto piled stones on the lee shore. Inside

the estuary the depth sounder told us our 7-foot keel was 6 inches

from dragging bottom.

Mangroves lined the shore. Thick. You could practically smell

the bugs over the wafting stench of raw sewage. 3 inches. I radioed

Jama for reassurance.

Hailing him twice the steady voice announcing Jama's presence

came on, "we are here to help you. We want you to proceed

past the concrete dock..." Who was we? Jama never said,

"my wife and I", or "me and the boys want you

to..." Just "we".

For me to try to approximate Jama would be to perform a severe

injustice to him and to our recollection. Sylvia and I were amazed

at the incredible long-windedness of his radio replies as he

guided us up this swampy, jungle river. Each natural marking.

A pier. A boat. Jama described it all with impassioned indifference.

By now I knew I had to avoid his spell at all costs. We were

in his grasp. He knew it and he knew we now needed him. "Evian,

we want you to anchor across from the cement pier. In line with

the channel marker, between the channel marker and the far shore."

I could hear the hum of the bugs, as the humidity of the day,

coupled with Jama's dulcet tones droned on. "We would like..."

I went forward to drop anchor. Sylvia stood at the wheel with

the boat in neutral. We were drifting slightly with the current.

Then we hit.

It's never a jolt. It's just that everything stops. Which is

strange, because on a boat nothing ever stops. You float here,

you bob there. This time, nothing. I got on the radio and called

Jama.

"Jama, Jama, this is Aviana. We seem to have run aground

at the moment."

At that he lost it. In anger Jama struck out, "Evian, I

told you to stay in line with the..."

He didn't tell us anything of the sort. He wanted to believe

he did. He wanted to believe that Jama was a cruising deity,

omniscient, guiding naive cruisers to a superior destiny. I knew

then that Jama had gone insane. Totally insane.

It took 20 minutes and a panga load of Mexicans with a 70-horse

Johnson to pull us backward off that mudslick. All to the sounds

of "Evian...Evian...do you copy?", coming across the

vhf handheld radio. We gave the Mexicans a bottle of Bacardi

for their efforts. We left the boat anchored but trapped in the

San Blas estuary due to an ebbing tide. We paddled the rest of

the way into town by kayak.

This morning I can hear the shouting cadences of the local Mexican

naval regiment somewhere across the mangroves. The sound of a

bugle, too. The inside cabin of the Aviana, now that the sun

has risen, looks to be filled with dust particles. The particles

are, however, blood sucking no-seeums. And they're eating me

alive.

High tide is at 10. With luck, we'll then be free to go. One

thing I've learned through the past 24 hours sitting on the jungle

estuary, with the humidity and bugs is this: Jama's command must

be terminated. Terminated with extreme predjudice.

|

|

|

We owe a debt of grattitude to brother Jay Duncanson, swimmer-with-manta

reys, whale-chaser, shark-dancer, for the patience and aptitude

he displayed in learning how to design a website and then teaching

us.

Without him you'd be doing something else right now. |

Photos

from Mexico

Photos

from Mexico Photos

from Mexico

Photos

from Mexico